Two likely democratic presidential contenders in 2020 have made quiet strides in recent years to bring into vogue a little-known policy that could reduce economic inequality — one that harnesses current law to expand workers’ ability to become owners in their place of employment.

Sens. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., and Kirsten Gillibrand, D-N.Y., have worked to advance legislation on employee stock ownership plans, or ESOPs, which are retirement vehicles that allow a business owner to sell their company stock to a trust co-owned by the company’s employees. The company typically purchases the owner’s shares with a loan, divides the shares among the staff, and then repays the debt annually with pre-tax payments from the company’s profits. When a worker leaves or retires, the company buys back that worker’s stock at fair market value, giving them a slice of the company’s capital earnings.

A bipartisan group of legislators first took up ESOPs in Congress in 1974, but when that generation of lawmakers retired, their successors did not embrace employee ownership with the same enthusiasm. The focus on deficit reduction, coupled with a few bad employee ownership scandals in the ’80s, ’90s, and early 2000s, led many otherwise receptive politicians to steer clear. Federal incentives for employee ownership began to dwindle, beginning under George H.W. Bush and continuing through the next three presidential administrations.

Last year, however, Sanders took up the mantle. He introduced legislationto expand state centers that provide training and technical support for establishing cooperatives and ESOPs, modeled off the successful Vermont Employee Ownership Center in his home state. Gillibrand also signed onto that legislation, which never made it through Congress.

This past summer, for the first time in more than two decades, Congress passed a pro-ESOP piece of legislation. Introduced by Gillibrand in the Senate and Rep. Nydia Velazquez, D-N.Y., in the House, the Main Street Employee Ownership Act makes it easier for small businesses to establish ESOPs and co-ops. It was included in the defense bill that President Donald Trump signed in August. (Another likely 2020 presidential contender, Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., introduced legislation this year for a different type of employee ownership. Known as co-determination, it would require companies with revenue over $1 billion to allow workers to elect at least 40 percent of their board of directors.)

Unlike conservatives, who have defended employee ownership on the grounds that it’s most certainly not socialism — indeed, it turns laborers into capitalists — liberals have taken to ESOPs because they strengthen worker power, boost worker income, and increase corporate transparency. Workers, the arguments goes, care as much about their employment as they do about corporate profitability, so they won’t advocate for a strategy that leaves them jobless, even if it is better for the short-term bottom line. “Simply put, when employees have an ownership stake in their company, they will not ship their own jobs to China to increase their profits; they will be more productive, and they will earn a better living,” Sanders said last year.

Some progressives have criticized ESOPs, with the argument that they are little more than tax breaks for corporations that don’t give workers real ownership of a company or a meaningful say in its management. ESOPs can also create tensions with traditional labor unions, as the latter seeks to organize workers, while ESOPs tend to blur the relationship between workers and owners.

Indeed, not many unionized ESOP companies exist. Some unions — like the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers and Steelworkers — have been open to the idea. Others, “like the [United Automobile Workers], are inherently distrustful,” said Loren Rodgers, executive director of the National Center for Employee Ownership, a national nonprofit based in Oakland, California. “In the auto industry, the threat of strikes is really important, and it’s harder to get people to strike against something when that might hurt the value of the shares in their retirement account.”

MORE THAN 14 MILLION current and former private sector workers have participated in ESOPs, according to the National Center for Employee Ownership. They work in almost every industry, from supermarkets, like the chain Publix, to policy research, like the firm Mathematica. About 7,000 companies today have the retirement plans. Research released earlier this year estimated that the average worker in an ESOP had accumulated $134,000 in retirement wealth from their stake.

Joseph Blasi, an economic sociologist who directs the Institute for the Study of Employee Ownership and Profit Sharing at Rutgers University, has long championed ESOPs because he believes they benefit both workers and companies, and are a way to transfer wealth to the middle class. Blasi points to studies showing that workers at ESOP companies tend to earn 5-12 percent more in wages than those at traditionally owned companies, have retirement accounts that are 2.2 times larger, and are far less likely to be laid off during economic downturns.

Sobering statistics about growing wealth inequality — like that the top 10 percent of households owns 80 percent of the financial assets, and the top 1 percent owns more wealth than the bottom 95 percent combined — underscore the need for economists, activists, and policymakers to figure out ways to counteract these trends.

“I’ve been working on them for over 40 years and only now have ESOPs become cool,” said Blasi.

A PAPER PUBLISHED this summer by a young economics researcher in Denmark has reinvigorated interest in ESOPs, as his findings suggest that the financial benefits of the retirement vehicle may be even greater than previously understood.

Esben Baek, who grew first interested in employee ownership after living in San Francisco and discovering pizza and bakery co-ops, pivoted from his traditional labor economics research to begin studying ESOPs in 2016.

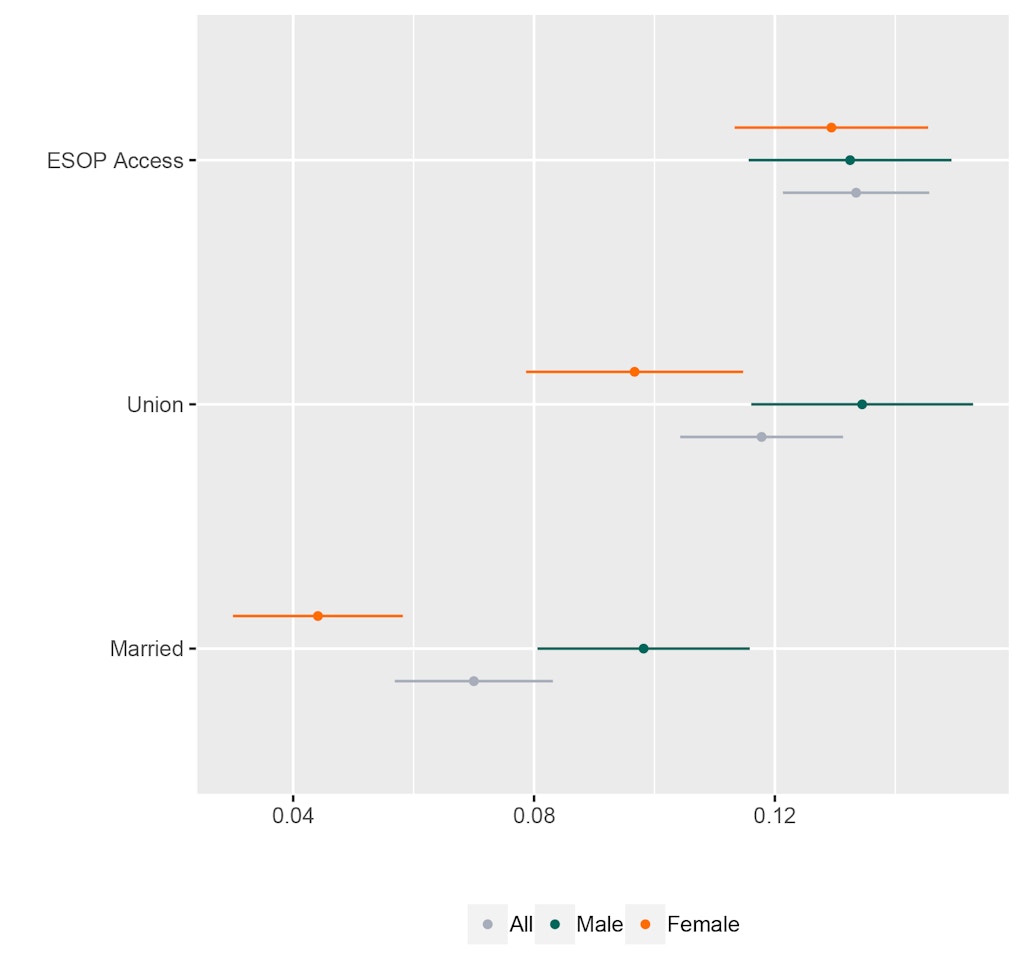

Baek’s University of Copenhagen master’s thesis makes use of a previously untapped data source: the 1997 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. He found that ESOP participation boosted wages for U.S workers by nearly 13 percent, much more than the 8 percent figure ESOP researchers typically cite. Baek also found that male and female workers enjoyed near-equal economic gains under ESOPs, more so than other variables, like union membership or being married, on the panel survey. Baek is presenting his research at an ESOP conference in New Jersey next month.

Douglas Kruse, a Rutgers University economist who studies employee ownership, was “thrilled and surprised” to learn of Baek’s work, he said, as it helps address a persistent issue that has plagued the ESOP community.

There have been many ESOP studies over the years, looking at things like productivity, employment stability, satisfaction, and organizational commitment. While the research has generally shown positive results, some economists have remained skeptical, because if workers have to decrease their wages and benefits in exchange for owning a piece of the company, then ESOPs would generally be considered too risky of a bet for workers to make.

Yet the existing empirical studies have suggested that isn’t the case; when scholars like Kruse and Blasi looked at cross-sectional and administrative data, workers who owned shares in their company also tended to have higher wages and benefits compared to those in non-ESOP companies. ESOPs appeared almost too good to be true, drawing skepticism from other economists about the underlying data.

“What Esben has done, the reason his data is especially good, is because with cross-sectional studies, maybe the workers are somehow better or they have higher credentials, and that’s why you see them receiving higher pay,” Kruse explained. “But with this national longitudinal data set, you can compare workers before and after joining the ESOP companies, and when you do, you see the pay goes up, and it appears to go down when they leave the ESOP.”

Kruse suggests this may be driven by the economic principle known as “efficiency wages,” in which ESOP companies recognize that paying higher wages on top of the employee-owned stock is really the most effective way to get more committed workers and boost productivity. “If a company establishes an ESOP but then cuts worker pay, then workers could start to see that as a financial risk,” Kruse explained. “Whereas if they get the ESOP on top of regular pay and benefits, then it’s like, ‘Hey, this company is doing well for me,’ and really helps create that sense of ownership and community.” Both Kruse and Baek agree that further research is needed to help explain what’s going on.

ASIDE FROM BEING a way to address inequality, the impending “silver tsunami” — the wave of baby boomer retirements expected over the next decade — is another reason ESOPs are gaining traction. According to a 2017 study by the worker ownership group Project Equity, 2.3 million businesses are owned by baby boomers who are approaching retirement, and these companies employ almost 25 million Americans.

While many of these business owners will fold quietly and sell their companies to competitors or private equity firms, ESOPs offer owners another alternative: selling the company to its workers. Advocates say this can help to better ensure that jobs remain in the local community, while still allowing the retiring owner to cash out. According to Project Equity, one-third of business owners over age 50 report having a hard time finding a buyer for their company. As a result, many just quietly close up shop, often without even considering selling their company to the staff.

But if ESOPs really can yield such positive results — for workers, owners, and local economies — why do they remain so obscure?

Most people have heard of 401(k) plans, a different kind of retirement vehicle authorized in 1978. Unlike ESOPs, employees pay for 401(k) stock through pre-tax wage deductions.

J. Michael Keeling, president of the ESOP Association, said 401(k) plans have been far more common among small businesses that offer retirement plans, because they require less overhead to administer properly. “Most nations have something like social security and a mandated retirement program every employer has to contribute to,” said Keeling. “But in America, retirement programs are voluntary, so businesses usually go for the cheaper option.” (According to the National Institute on Retirement Security, about 45 percent of all U.S. households have zero retirement savings.)

Most people with ESOPs also have 401(k) plans, a recommended best practice to reduce financial risk. It’s not good for workers to have their retirement savings wrapped up in the fate of a single company, as the Enron disaster of 2001 showed. “There’s no question in my mind that if a worker has holdings in an ESOP, they should have a separate, diversified 401(k),” said Blasi from Rutgers University. “What we say, though, is that workers who have both accumulate more for retirement than workers with just one.”

One study, published in 2010 using Labor Department data, compared roughly 4,000 ESOP companies to all other non-ESOP companies with 401(k) plans. The researchers found the net assets per ESOP participant to be 20 percent higher.

“We’ve got a marketing problem,” said Rodgers from the National Center for Employee Ownership. Rodgers’s group was founded in 1981 and has spent most of its time conducting research and connecting worker-owned companies with one another. Since 2010, though, the organization has been trying to play a bigger role in getting the word out.

Rodgers has a few theories for why ESOPs aren’t more well-known. Some of it he chalks up to the incentives of the business adviser world: If you’re a broker, like an investment banker or personal wealth adviser, the fees you take home at the end of the day would be higher if you encourage your client to sell their company to a private equity firm or another corporation, rather than their employees, he said. Financial advisers also tend to advise owners on things they know how to do themselves, and ESOPs are highly regulated, complex structures. “If you, as a CPA, advise a business owner to sell to their employees, you’re probably advising them on something you personally don’t know how to do,” said Rodgers.

From the owner’s perspective, selling one’s company to an outside firm is generally going to be a more lucrative option, and often easier, than creating an ESOP, Rodgers explained. “It’s hard to say no to more money, and it certainly can look easier, because you just sell your business and walk away.”

Further complicating things are several past ESOP scandals that haunt the field. One such incident occurred when United Airlines went bankrupt in 2002, leaving its employees with ESOP stock in the lurch. In some other cases, owners who sold their company to their employees had their businesses assessed at way too high of a value, so that when they sold their shares to an ESOP, they made off like bandits and left the workers paying an outsized loan. But the Labor Department has been cracking down on that overvaluation issue, and since 2014 especially, ESOP advocates say, worker safeguards have grown to be far more defined.

A number of groups have been ramping up efforts to educate the public and the business community about employee ownership. This past spring, Rutgers University approved the establishment of the Institute for the Study of Employee Ownership and Profit Sharing, the world’s first research center of its kind. In 2016, the Pennsylvania Center for Employee Ownership, the nation’s first state center dedicated exclusively to promoting awareness of ESOPs and co-ops, was founded. Kevin McPhillips, the executive director, told The Intercept that he travels around talking to businesses and elected officials, trying to help get the ESOP and co-op message to owners who are beginning to plan for retirement. A few other state centers have long existed to provide technical assistance to worker-owned companies, like those in Vermont, Ohio, and Colorado.

It’s well past time for leaders to take the prospect of employee ownership more seriously, Blasi says. “It’s not a panacea, but neither is regulatory reform or raising the minimum wage.”

Per approfondimenti: European Federation of Employee Share Ownership

Follow

Follow